By Sana Haroon

Why would anyone want to walk for days in the land of ice and rock, with no comfort, no guarantee, and only uncertainty ahead. Why chase a mountain that doesn’t promise anything in return. Why risk it – for something so few will ever understand.

Before I even set foot on the trail, a sense of shared questions filled the space. And yet, none of them were stronger than the quiet voice inside me that simply said—go.

The Karakoram does not call loudly—it whispers. A whisper strong enough to unsettle your heart, to make you restless until you follow it. That’s how my journey to Concordia—the foot of K2—began.

I won’t deny it—I was stepping into risk. Floods were rising in the valleys, I was not the fittest, not the most experienced, and definitely not the most prepared, and financially, I had put in everything I had. Yet the question that stayed with me was – how could I not?

Despite all that, there was something stronger: a quiet pull toward the mountains, an urge to test my limits, and to find silence far away from home.

Talking about uncertainties—it only grew when I landed in Skardu and learned that two people who were supposed to join me had backed out due to the flood situation. Suddenly, I was left with two choices: return home or go all alone. Yes, you heard it right—alone on a 12-day K2 trek, with not much prior experience.

Just two days earlier, the plan had already shifted. I had to change my flight details, fly out a day earlier, and then spend long hours waiting at the airport when my flight got delayed. By the time I finally landed—three hours late—I was hit with the bad news. To make things worse, I also found out that one of the bridges we needed to reach our first campsite by jeep had been swept away by the floods. It was complete chaos.

I gave myself some time to think, weighed the risks, and decided to step onto the trail alone. And here I must add: the company I chose was Baltistan Tours whose founder Muhammad Iqbal Balti is an intellectual, social activist, season politician and the founder of responsible tourism in Gilgit -Baltistan.

—were trusted and well-known people. Otherwise, I would never recommend anyone to take such a risk with people you don’t know or trust completely.

When I first thought about going to Concordia, it felt almost impossible. I didn’t know who I would go with. How could I join a group of strangers? How would I be allowed to stay away from home for two weeks? I didn’t even have friends who shared the same interest. And then, of course, there was a big financial cost. So, I pushed the thought deep into the back of my mind., as something that might never become reality—at least not anytime soon.

But the beautiful thing about life is that when Allah wills something, paths are carved, doors open, and everything falls into place in the most unexpected yet magical ways.

That’s where the long days of trekking began. Each day had just one goal: to reach the next campsite. Every step took me closer to that mighty mountain, every breath felt harder, and every moment showed me a place as raw as it was beautiful.

Skardu to Askole: We started our journey from Skardu city (about 2,500 m), leaving very early to cover most of the route before the water levels rose from the glaciers melting under the sun.

Our first campsite was Askole (around 3,040m)—a 6–7-hour jeep ride from Shigar District in Baltistan. Beyond Askole, there are no villages, towns, or permanent houses—only temporary camps set up by trekking and climbing expeditions. From here, all supplies, porters, and donkeys are arranged before moving forward. In short, Askole marks the end of permanent human settlement and the beginning of the wilderness in the Baltoro region.

Luckily, we did not encounter any roadblocks from landslides, and the drive went smoothly until we reached a point where the bridge had been swept away. There, we left the jeeps and walked for 2–3 hours across the mountain to reach the other side. Our porters carried the luggage with us, while jeeps waited ahead the first part of the walk was tough—the incline was steep, and my body hadn’t warmed up yet, which made it harder than I thought. Once we got across, another jeep was waiting, and by noon we reached Askole, safe and sound. The rest of the day was spent wandering around the beautiful village and getting ready for what lay ahead.

Askole to Johla: From here on, the routine was simple: wake up around 5–6 AM, have breakfast, and walk for an average of 8–9 hours. The trek from Askole to Jhola was easy to moderate. Being at a lower altitude, the heat made it harder than expected—the sun was brutal, and walking straight for hours under it was exhausting. A neck gaiter, sun hat, and sunglasses were a must. Thankfully, the trail itself wasn’t too challenging.

By the time we reached our second campsite, Jhola (about 3,100 m), I had started adjusting to the surroundings and no longer feared being alone. The campsites were often crowded, but I found that the fewer the camps, the better the view you got to enjoy. Every day, for next 10 days, on reaching camp, we were welcomed with amazing tea and a warm evening supper prepared by our cook, Muhammad —nothing fancy, but it felt perfect out there.

Johla to Paiju: Our next destination was Paiju (about 3,420 m), a common acclimatization campsite. The trek was moderate overall, except for the last steep incline we had to climb to finally reach the site. Like Jhola, it was still at a relatively low altitude—hot, dusty, and dry. Paiju marked the final touch of trees before stepping into the true wilderness. Getting there took us almost nine hours.

The following day was a rest day, and this campsite felt like the most crowded campsite of all. Unlike others, it even had a few basic facilities: a running water tap (that’s where you learn to appreciate the smallest things you normally take for granted), makeshift tin toilets that actually closed, and a huge tank storing glacier water where people even managed to bathe. The temperatures were mild, making it comfortable to sit outside and enjoy the surroundings.

The rest day was about relaxing, acclimatizing, taking a short nature walk, doing some much-needed laundry, and of course—eating. And the highlight? Our cook Muhammad somehow baked pizza for us in the middle of the Karakoram.

Paiju to Khoburtse: From Paiju onward, the trail changes and gets tougher. You step onto the mighty Baltoro Glacier, a vast, uneven ocean of rock and ice. The landscape turns wild, with giant granite peaks with sharp and dramatic edges rising around you. But nothing comes for free up here. That day was especially hard—long hours of walking on a demanding trail.

The weather was unpredictable. It had been raining throughout the day which made difficult for us to cross glacier. Also, there was continuous rock falling due to rain. It was cold, wet, and felt like the trail would never end. We carried packed lunches—boiled eggs, potatoes, and some cheese.

After about four hours of trekking, we stopped at the Liligo campsite, where most groups usually break for lunch. My rain jacket was drenched, there was no real shelter, and people were running around trying to serve food. Then someone handed me a cup of hot tea and noodle soup. It’s hard to describe how good it felt in that moment to hold something warm.

After that, we kept going, making a quick stop later to eat our packed lunch. From Liligo to Khuburtse (about 3,795 m) was another four to five hours of trekking through rain, cold, and winds. Still, the landscape was unlike anything I had seen at the previous campsites—raw and breathtaking.

When we finally reached camp, I went straight to the kitchen tent where a stove fire was burning. After a hot cup of tea, I changed into warm base layers, which I ended up wearing for the rest of the trek to stay warm and dry.

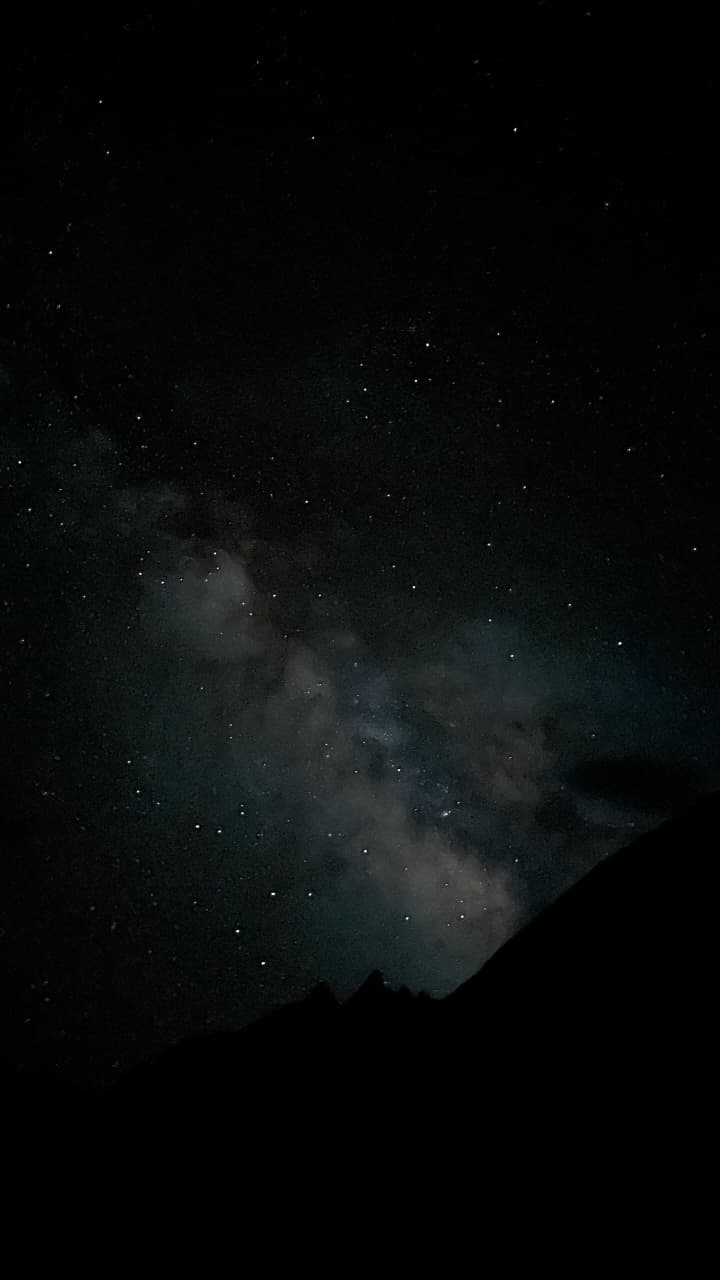

I checked off another wish on my wishlist when I woke up around midnight to the sound of rain at Khoburtee Camp. There was something so comforting about the gentle tapping of rain on the tent—it was a simple experience I had been wanting to feel for so long.

Khoburtse to Urdukas: The trail grew harsher and more rugged as we moved past Khoburtse. It was still raining, with the sky and peaks hidden under heavy clouds. The path was much like the day before, except now we had to walk across giant rocks with no clear trail. It was another tough day, but with every step, new and amazing views unfolded.

On the way, we crossed two glaciers. One of them was unforgettable, a stretch of clear white ice that looked almost unreal.

By the time we reached Urdukas (about 3,990 m), the sky had begun to clear, and at last I could see the dramatic Trango Towers rising sharp and tall, along with other granite peaks. The campsite itself was breathtaking.

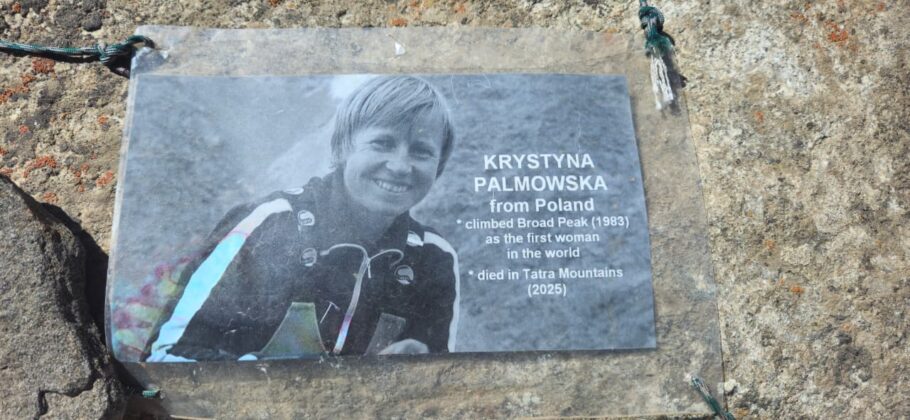

There was also a small memorial at the camp, honoring those who lost their lives here due to rockfalls or during expeditions to Broad Peak—a quiet reminder of the risks and respect the mountains demand.

Urdukas to Goro II: Past Urdukas to Goro II (about 4,295 m), there is no soil, no greenery—only ice, rocks, and the roar of glaciers. The campsite sits right on the glacier itself. It was the sixth day of my trek, and I started feeling a bit lost. I wanted to see the sun and a clear sky, but all around me were heavy clouds, black glaciers, rocks, and ice. My legs and feet were exhausted from walking on uneven surfaces.

There was no phone signal, no green pastures, no clean toilets or clothes, no showers, no basic facilities—just the fixed routine of waking up to alarms and walking for the rest of the day. In short, you start missing home and feel a bit homesick.

Goro II to Concordia: After a few days in this completely different world, you start to feel on the edge of a mental breakdown, and sometimes you just want it all to be over. This may not be the same for everyone, but I felt it for the first time when I reached Goro II. On top of that, sleeping on ice with small rocks pressing under my sleeping bag gave me chills that lasted through the night. There comes a moment when you start counting even the smallest blessings, like having a cozy bed with a soft mattress. If you need anything, you have to dig through your bag, unpack, repack, and unpack again—all with an exhausted body and aches in every inch. After several days of this, it all starts to feel like too much.

The trek from Goro II to our final destination, Concordia (about 4,650 meters), was the most challenging day so far. My whole body felt completely drained, and even a single step seemed to take all my energy. But more than that, my mind wasn’t in the right place—I didn’t even realize how far I had come, how close I was to finally seeing mighty K2.

Like every day, I picked up my bag, put on my trekking gloves, unfolded my trekking poles, laced up my boots, and started following my guide along the never-ending trail. The day began well. Despite the aches, I felt blessed to be healthy, free from sickness or altitude problems, and still able to walk on my own.

On the trail to Concordia, I got a clear glimpse of Giant Broad Peak—one of the 14 mountains in the world above 8,000 meters. Before this, I had only seen it in pictures and movies. Seeing it in real life, you immediately understand why it is called Broad Peak. Getting closer, it feels like a massive snow-covered giant.

You might ask yourself, ‘Why can’t I see K2 yet? Where is it?’ And that’s the thing—K2 demands all your energy just to be glimpsed. That’s how special it is. You keep walking for hours, yet you can barely see it until you finally stand at Concordia.

After 7–8 hours of walking on ice, we still hadn’t reached Concordia. I could barely take another step—I was completely done for the day and clearly not in great shape. Here, I have to mention my guide, Musa Khan, who played a huge role in making this journey possible and ensuring I reached my destination and returned safely. From making sure I drank only boiled water and plenty to stay hydrated, to keeping my meals high in protein, to feeding me tons of dried fruits on the trail to maintain energy, to managing every aspect of the trek and putting my safety first—in short, being a friend, a brother, and acting as a father wherever the situation demanded

Our cook also deserves a huge mention—preparing delicious meals at such high altitudes, from samosas to pizza, Chinese dishes to vegetables, sweets after lunch, and simple yet thoughtful packed lunches for the trail. Another perk of being on my own was that I got to eat what I liked and could share my food wishes. He even carried my bag when he could. None of this would have been possible without the incredible support they provided every step of the way.

And when the moment finally came, I couldn’t even grasp it at first—that this was it, right in front of me. The mountain I had read about, seen in pictures, and imagined a thousand times in my heart. And now here I was, living that dream. What had once been a distant thought, a quiet wish, to see mighty Mt. K2 with my own eyes, had become real.

After days of trekking through glaciers, rugged paths, and unpredictable weather, I was finally at Concordia, standing face to face with the world’s second-highest peak. K2 loomed above me. They call it the throne room of the mountain gods—and that day, I had the honor of standing in it, a tiny human in the shadow of one of the greatest wonders of the world.

The next day, we took a rest day at Concordia, and I even baked a cake to celebrate this amazing journey. Looking back now, it all feels like it went by so fast. Once you return, you feel an even stronger urge to experience it all over again. You realize that no matter how much effort you gave at the time, there’s always more to see, more to feel, more to experience. That’s the power of love for the mountains—it’s never enough. They test your limits, push you to your edge, and yet you crave more.

It’s impossible to put every moment into words, because it was such a long, intense journey, but this is the story of reaching Concordia. And yet, the journey doesn’t truly end here—you still have to make your way back along the same paths. What happens on the return to Askole is another long story, and perhaps one I’ll share in another piece.

This journey wasn’t a walk in the park—definitely not for everyone—but it’s so worth it that you leave a piece of yourself up there, and all you can think about is going back, a hundred times over.