By Khalid Khan

In the mist-laden valleys and towering peaks of the Hindu Kush, where time has often stood still, lies the forgotten story of a land once known as Great Kafiristan. Today, its remnants linger only in whispers, in the scattered enclaves of an ancient people whose beliefs, languages, and ways of life have been eroded by the tides of conquest, conversion, and assimilation.

Great Kafiristan was not a fixed entity in geography; its boundaries shifted with time, conquest, and resistance. At its zenith, it stretched from the verdant valleys of Kashmir to the rugged landscapes of Kapisa, from the bustling corridors of Peshawar to the isolated heights of the Wakhan Corridor. But from the 10th and 11th centuries onward, a relentless series of religious wars, spearheaded by Persian and Afghan invaders, began to shrink this land. By the late 19th century, only present-day Nuristan and the Kalash valleys of southern Chitral remained. The final blow came in 1895, when the iron-fisted Emir of Afghanistan, Abdur Rahman Khan, launched his campaign against the last strongholds of Kafiristan, forcing its inhabitants into conversion and annexing the land into his dominion. What remains now is but a fragment—preserved only in the isolated Kalash valleys, where traces of a once-flourishing culture still survive.

The names Nuristan and Kafiristan, given by outsiders, obscure the true identity of this region. Historically, it was known as Great Baloristan and Dardistan—terms that carried echoes of antiquity, referenced in Sanskrit texts as Dard Desa, and in Arab chronicles as Baloristan. The term Kafiristan is a later construct, born of the need for justification—used by invaders who sought to wage wars in the name of faith, branding the indigenous people as infidels to validate their campaigns. What followed was nearly a millennium of conflict, where the native inhabitants of Gandhara and Uddiyana were forced to abandon their ancestral lands, retreating into the impenetrable mountains. The wars of faith did not merely claim territories; they uprooted entire civilizations, erasing ancient beliefs, traditions, and languages that had once flourished.

Waigal, one of the surviving centers of the Kalasha Ala-speaking people, was not always their domain. Before their arrival, it was a stronghold of the Gawar people, whose presence extended westward into the valleys of Kunar, Arandu, and Doklam. The arrival of the Kalasha Ala—often referred to as the “Black-Robed Kafirs”—triggered a displacement, pushing the Gawar-speaking communities toward the fringes. Even today, remnants of these displaced people, identified as Gauri, Gawar Bati, and Gabr, can be found in upper Swat, Dir, the Abasin valleys, Chitral, and Kunar. The traditions of the Kalasha Ala and other Nuristani groups themselves corroborate this history, acknowledging that they too were once outsiders who claimed these lands. The Kalasha Ala’s historical footprint extended even further, reaching into Wakhan and, by the 14th century, launching incursions into Chitral—evidence that these enigmatic people once roamed far beyond the present-day confines of Nuristan.

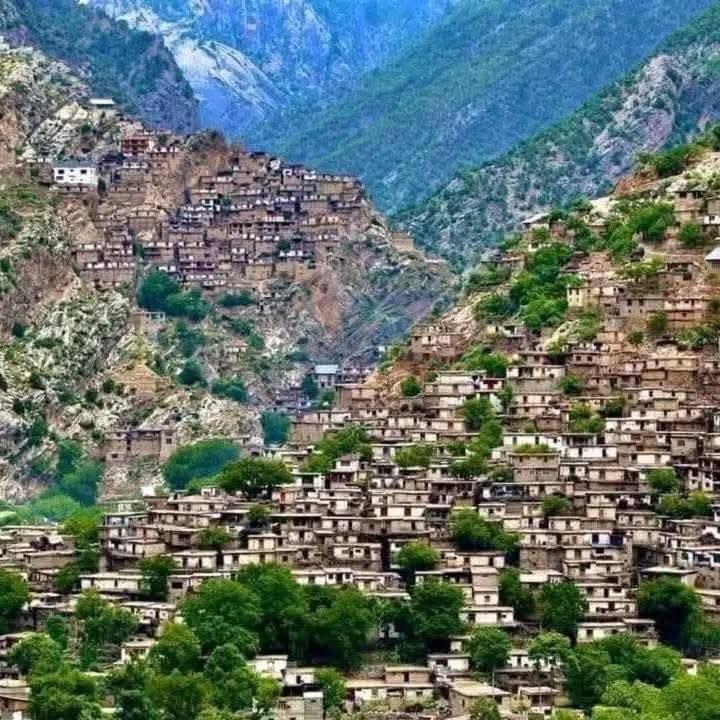

The architectural landscape of this lost civilization tells its own story. Like Waigal, many villages of old Baloristan and Dardistan—particularly in Swat, Dir, and Kunar—were built on steep mountain slopes, inaccessible to outsiders and strategically positioned for defense. These settlements, unlike the open plains, were fortresses of survival. Their rear and flanks were guarded by sheer cliffs, their fronts secured by rivers and streams that served as natural barriers against invaders. This pattern of high-altitude habitation was not by choice but by necessity. For centuries, these people lived under the constant threat of raids and forced conversions, and their villages were designed as sanctuaries of last resistance. Even in the early 20th century, the remnants of these ancient defensive strategies could still be observed in the settlements of Upper Panjkora, where houses clung to steep inclines, their rooftops forming terraces for the homes above them—a testament to an era when survival depended on the land’s topography.

Time has not been kind to the legacy of Great Kafiristan. What once spanned vast territories, harboring diverse tongues and traditions, has been reduced to isolated echoes in the valleys of Chitral and Nuristan. The forced assimilation of its people, the erasure of their beliefs, and the loss of their linguistic and cultural heritage serve as reminders of how fragile human civilizations are when confronted by the unrelenting march of history. Today, the Kalash, one of the last living vestiges of this lost world, stand as custodians of an ancient past—keeping alive, however tenuously, the memory of a civilization that once defied time, faith, and empire.