The close outcome of Pakistan’s election and resulting near-term political uncertainty may complicate the Country’s efforts to secure a financing agreement with the Internatinoal Monetary Fund (IMF) to succeed the Stand-By Arrangement (SBA) expiring in March 2024, says Fitch Ratings.

A new deal is key to the Country’s credit profile, and we assume one will be achieved within a few months but an extended negotiation or failure to secure it would increase external liquidity stress and raise the probability of default.

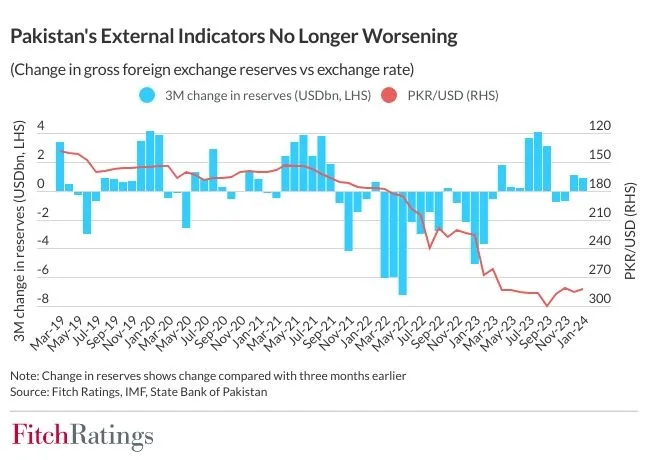

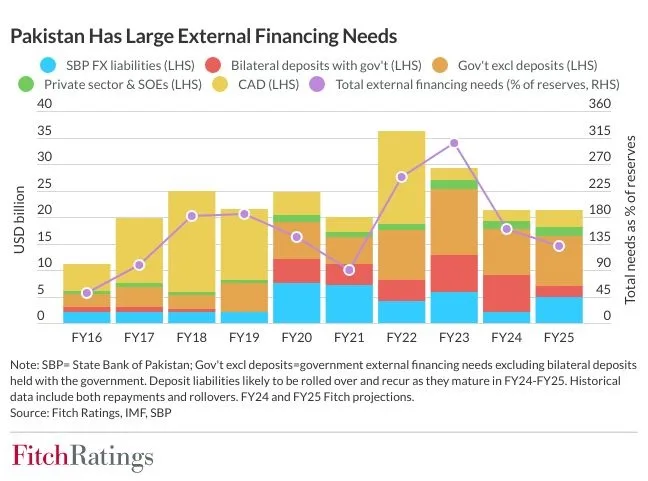

Pakistan’s external position has improved in recent months, with the State Bank of Pakistan reporting net foreign reserves of US$ 8.0 billion as of February 09, 2024, up from a low of US$ 2.9 billion on February 03, 2023. Nevertheless, this is low relative to projected external funding needs, which we expect will continue to exceed reserves for at least the next few years. We estimate Pakistan met less than half of its US$ 18 billion funding plan in the first two quarters of the fiscal year ending June 2024 (FY24), excluding routine rollovers of bilateral debt.

The sovereign’s vulnerable external position means that securing financing from multilateral and bilateral partners will be one of the most urgent issues on the agenda for the next government. This looks set to be a coalition of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) and Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) despite the strong performance by candidates associated with Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party in the election. Negotiating a successor deal to the SBA and adhering to the policy commitments under it will be critical to most other external financing flows, not just from the IMF, and will strongly influence the Country’s economic trajectory in the longer term.

Finalising a new IMF deal is likely to be challenging. The current SBA is an interim package and we believe any successor arrangement would come with tougher conditions which may be resisted by entrenched vested interests in Pakistan.

Nonetheless, we assume any resistance will be overcome, given the acute nature of the country’s economic challenges and the limited alternatives.

Continued political instability could prolong any discussions with the IMF, delay assistance from other multilateral and bilateral partners, or hamper the implementation of reforms. We believe a government will assume office and engage with the IMF relatively quickly, but risks to political stability are likely to remain high. Public discontent could rise further if PTI remains sidelined – the election revealed continued strong public support for the party.

Pakistan’s governments have a poor record of completing IMF programmes – less than half of its 24 IMF programmes have disbursed more than 75% of the funding available. However, there has been fair progress on targets under the current SBA.

Moreover, we perceive there is stronger consensus within Pakistan on the need for reform, which could facilitate the implementation of a successor arrangement.

Policy risks could rise again over time if external liquidity pressures ease, either as a result of initial reform successes or developments outside Pakistan, such as a substantial drop in oil prices. This could lead to the renewed build-up of economic and external imbalances. We believe Pakistan’s external finances will remain structurally weak until and unless it develops a private sector that can generate greater significantly more export income, attract FDI or reduce import dependence.