By Agha Iqrar Haroon

I am at the last leg of my life but I will leave behind the music that will remain with you for all times to come — Surinder Kaur—Toronto 1998 live show

“Mavan te dhiya ral biathya ni maye”, a Punjabi song recorded on Radio Pakistan Lahore in 1943 is still the best-ever written and sung song representing anthropological aspects of the mother-daughter relationship of agrarian Punjab and still makes Punjabi mothers and daughters cry while listening this song.

This song is a living memory of my mother and listening to this song always connects me with my mother who died on December 21, 1981. Whenever my mother used to sing this song, I saw her weeping. I could not understand the reason and relationship of this song with my mother’s tears. Now at the age of 55, I may feel the pain and memories that could link some stanzas of this song with the innate motherhood of my mother. My mother lost her mother when she was just 12 years old.

Having two younger sisters aged nine and seven, she brought them up with the support of my maternal grandfather who decided not to go for remarriage after the death of my maternal grandmother. Brought up in a protected family at Paisa Akhbar building, Urdu Bazaar Lahore with lots of cousins, my mother had almost everything in her life being the eldest daughter of Maulana Hifzur Rahman Paisa Akhbari but she had no mother with whom she could sit and share herself. She had no brother but her male cousins loved and respected her as their eldest sister till her last breath. After finishing her A-level from the then most expensive girls school “Lady Maclagan Girls High School, Lodge Road, Old Anarkali, Lahore, my mother was married in 1950.

My mother must have been 13 or 14 years old when the song “Mavan te dhiya ral biathya ni maye” (mother and daughters are sitting together) was recorded at Lahore Radio station in 1943 and being a daughter of an affluent family, she must have had radio and must have listened to this song at a very young age when she had already lost her mother and was acting as a mother of her two younger sisters.

Sung by Parkash Kaur and Surinder Kaur, this song became an instant hit and it is still as popular as it was in 1943 and thereafter. The young singer Surinder Kaur and my mother were both born in the same year—1929 and lived in the same city—Lahore and not very far away from each other because walking distance from Paisa Akhbar building to Bashan Street Chuburji is hardly two miles. However, I am sure they had never met each other but the song “Mavan te dhiya ral biathya ni maye” connected both of them forever and my mother kept singing this song till the last months of her life. Another factor in the lives of Surinder Kaur and my mother is strangely similar. Surinder Kaur became a widow when she was just 47 years old while my mother became a widow at the same age when my father died at the age of 52 in 1977. However, my mother could not survive without my father for long and she died just after four years her husband’s death.

In one of her interviews, Surinder Kaur mentioned that her mother used to sing “Mavan te dhiya ral biathya ni maye” and this was the reason that when Surinder Kaur had the first opportunity for Radio recording with her eldest sister Parkash Kaur who was already a known Radio voice, Surinder decided to record folksong “Mavan te dhiya ral biathya ni maye”.

Surinder Kaur’s life is documented by her eldest daughter Dolly Guleria in the form of a printed book as well as an audiobook and my contact with her granddaughter Sunaini Sharma (daughter of Dolly Guleria) was helpful in rechecking certain facts about Surinder’s life. Therefore, for me, this article is a story of two mothers—-my mother and the mother of Surinder Kaur who used to sing “Mavan te dhiya ral biathya ni maye”. Actually, this folksong links every Punjabi mother with her mother and her daughters—A song that beyond any iota of doubt became eternal through the voices of Parkash Kaur and Surinder Kaur.

The story in this article has multiple dimensions as it is a story of pains and agonies left behind by the division of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 and the rise of an urban Punjabi girl of an educated family as the voice of both the Punjabs and her contribution for documenting anthropological aspects and oral wisdom of Punjabi culture through her songs.

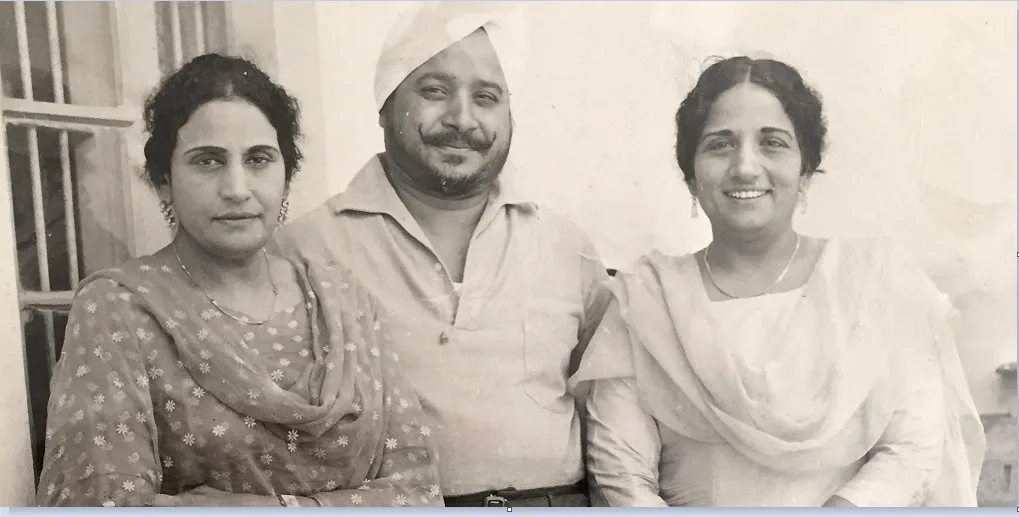

Born in Lahore on November 25, 1929, Surinder was raised with her four sisters and five brothers at Bashan Street Chuburji Lahore. Her father was a chemistry professor at Government College Lahore. Surinder Kaur was an urban Punjabi girl from Lahnda Punjab (West Punjab) who was raised in a well-educated family in Lahore city but contributed her whole life to documenting and saving classical Punjabi language and collective Punjabi consciousness through her songs.

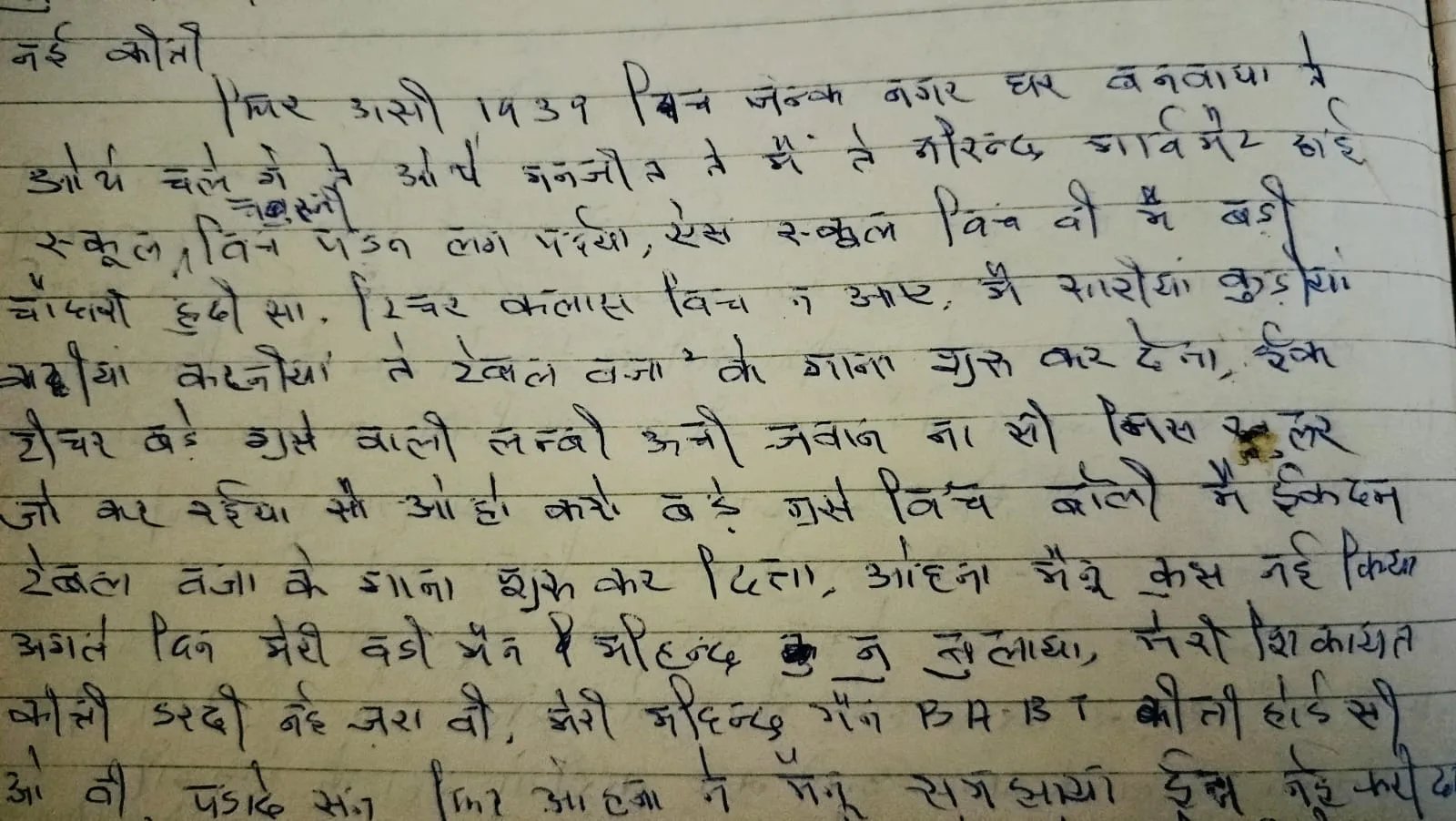

Surinder Kaur wrote some of her memories when she was living abroad with her daughter.

According to these memories, she spent the early years of her education in Victoria School Lahore which is now known as Victoria High School. She added that in 1939, she moved to Arya Nagar Girls High School in Lahore.

Government Victoria Girls’ High School, is in Haveli Nau Nihal Singh. Dating from the Sikh era of the mid-19th century, the haveli is considered to be one of the finest examples of Sikh architecture in Lahore and is the only Sikh-era haveli that preserves its original ornamentation and architecture. It is situated at Circular Road, Mohalla Sathan Walled City of Lahore.

She did her matriculation at Arya Nagar Girls High School Lahore which was an English Medium School and was in the vicinity of Choburji Garden. The school was established in the same year (1929) when Surinder Kaur was born. Having a total area of 14 Kanal of land, 10 Kanal was an open area (grounds) and the building was spread over four Kanal in 1929. The school was renamed after the division of the Indo-subcontinent as “Govt Girls High School Choburji Garden Lahore”.

Surinder Kaur’s paternal and maternal grandfathers belonged to educated families of Lahore, mostly working in the Railways and Education Department of the undivided sub-continent. Her two aunts and one sister were also in the profession of teaching. A free soul by birth, Surinder Kaur had no such love with studies but she was an intelligent girl and therefore got good grades in school although she used to spend most of her time playing in the school garden instead of being a studious student.

A book written by her daughter Dolly Guleria titled “Wagdey Paaniyaan Da Sangeet (Music of Flowing Rivers) is the most authentic documentation of the life of Surinder Kaur.

After the division of the Indo-subcontinent in 1947, Surinder Kaur and her parents relocated to Ghaziabad, Delhi. She was married to Prof. Joginder Singh Sodhi, who was born and raised in Gujranwala. Spotting her surprising talent, Prof. Joginder Singh Sodhi became her support system, and soon she started a career as a playback singer in the Hindi film industry in Bombay, introduced by music director, Ghulam Haider. She got an extraordinary response for her Hindi and Urdu songs in the 1948 film Shaheed, including “Badnam Na Ho Jaye Mohabbat Ka Fasaana”, “Aanaa hai tu aajaao” and “Taqdeer ki aandhi” and “Hum kahaan aur thum kahaan”. However, her soul was connected with Punjab and Punjabi, and she eventually moved back to Delhi in 1952 and dedicated her life to reviving Punjabi songs. Got fame from singing Hindi and Urdu songs, Surinder Kaur decided to switch to Punjabi when she was the most popular voice of Urdu and Hindi songs. The force behind her decision was to preserve, promote, and document the Punjabi language. She thought that the Punjabi language was losing its social status and classical diction was vanishing from songs and literature. Her contribution to the Punjabi language is yet to be documented properly.

To my understanding, her biggest sacrifice for the Punjabi language was that she left singing Urdu and Hindi songs and dedicated herself to Punjabi songs at the time when she was a shining star of the Urdu and Hindi songs industry. At a very young age, her voice became the most popular while singing with names like Syria, Muhammad Rafi, Lata Mangeshkar, and Talat Mahmood.

Surinder Kaur’s husband Prof. Joginder Singh Sodhi who did his first master’s in Psychology, left his job to get a master’s degree in Punjabi language because he was the mentor of his wife—Surinder, and wanted to produce Punjab’s wisdom and culture in lyrical form that had not been produced and sung before. His love for Surinder was the driving force behind Surinder’s confidence and success.

Her daughter in her book stated that her father (husband of Surinder Kaur) continued to guide her singing career while Surinder Kaur in one of her interviews said:

“He (Prof. Joginder Singh Sodhi) was the one who made me a star. He chose all the lyrics I sang and we both collaborated on compositions, we wrote together such classics as “Chan Kithe Guzari Aai Raat,” “Lathe Di Chadar,” “Shonkan Mele Di,” and “Gori Diyan Jhanjran”, “Sarke-Sarke Jandiye Mutiare”.

Prof. Joginder Singh Sodhi was an activist and popular among communists of India and his residence was a popular “Baithik” (sitting place for guests) for left-wingers. The Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), which was an arm of the Indian Communist Party in Punjab was strongly supported by the couple through their appearances in remote villages of East Punjab and both helped IPTA socially and economically.

Alas, the untimely death of Prof. Joginder Singh Sodhi at the age of just 52 in 1976 left Surinder unguarded and in a chaotic state of mind when she was just 47 years old mother of three daughters. Her daughter and granddaughter believe that after the death of Darji (Prof. Joginder Singh Sodhi), Surinder never recovered from the trauma of her husband’s death till she departed from this material world. An ever-smiling, witty, jolly, and full-of-life woman spent the rest of her life with the memories of her husband and the 12,000 books he left behind in a rented house. For months, Surinder did not reconcile with reality and she sometimes used to tell her daughters that Darji would come back soon. What an agony of an over-protected wife who used to leave all responsibilities of her professional life as well as home to her caring husband, when she had been ruling the performance stages all over the world. Darji used to write lyrics for her, used to choose the best ideas and content of Punjabi literature, and even used to create tunes for her songs along with her performing team. Darji used to cook the best of the best food of her choice when she was out for performance and she knew that she would go home and Darji would offer her the mouthwatering food she had desired to eat before departing for performance. This lioness of the stage lost everything with the death of her lion. Life was hard after 1976 for Surinder because she had to face more disasters like the deaths of her eldest sister and first teacher in music Parkash Kaur and then another sister who used to sing duets with her died due to cancer.

Her daughter in her book explained that the untimely death of Prof. Joginder Singh Sodhi was a great disaster for Kaur because, like any legend of the Communist Party, they were not well-off economically, living in rented houses and surviving on what they had been earning together. There is no doubt that the friends of Prof. Joginder Singh Sodhi were a strong support system for her but she had no habit of asking any favor from anybody and being a widow she kept a distance from everybody because she had three daughters and no son. Her daughter wrote in her book that Surinder Kaur got very cautious in her life after the death of her husband. Her daughter mentions that her collaborators in music like Asa Singh Mastana, Harcharan Grewal, Rangilla Jatt, and Didar Sandhu were very close friends of his father. They supported Surinder Kaur and helped her to come out of the trauma of the death of her husband when she decided not to sing after the death of her husband but friends and family of her husband helped her to come back in singing. Kaur in several interviews confirmed that she never thought to live without Prof Sodhi who was her mentor, friend, husband, cook, writer, musician, lyrist, manager, teacher, advisor, admirer, and almost everything in her life. She stated that Prof Sodhi used to cook the food she loved to eat whenever she returned from foreign or intra-city tours. She said that even performing the last song of any event, she had been thinking that now she would go home where “Darji” would offer her excellent food, daughters would hug her and she would inform every nitty-gritty of her tour to all of them and Darji would listen to her with smiling face.

In December 1977, Surinder Kaur bought her house with the amount the University gave her after the death of her professor husband. It was in the vicinity of Model Town Delhi where she lived with her daughters until this area came under unplanned construction of the Delhi Metrorail project. The original Delhi Master Plan was changed to accommodate this new project and residential areas that had been legal for decades came under this diversion from the Master Plan the government decided to demolish certain residential areas for laying the track and Surinder Kaur’s home was marked for demolition. However, through a legal fight, this part of Mall Road was taken out of the demolition plan but the whole scene made her scared about the fate of her only shelter. Therefore, she decided to sell this house and started living with her eldest daughter Dolly. There is no doubt that her life was a story of constant struggle after the death of her husband. However, from 1976 till her death, Surinder lived because she had to live for her three daughters but without having the desire to live anymore. In her hard times, a music promoter from Canada– Iqbal Mahal helped her with her shows, and Surinder Kaur in her interviews said “Iqbal Mahal is my puttar (son) and their mother-son relations continued till her death.

In 1997, she visited Lahore and the then Prime Minister Mian Nawaz Sharif hosted her in her natal place and she recorded a show at PTV Lahore. The Punjab government managed her visit to her home “Maya Bhawan” (constructed in 1902) where she spent almost the whole day with tears in her eyes—what an honor visiting her birthplace whose title is after the name of her mother and the street is after the name of her father– Bashan Street. Two days before coming to Lahore, she had gone through a serious dental surgery and her jaw was swallowed and doctors advised her not to travel and to avoid any singing. However, she refused both pieces of advice and told her family that she could not miss the chance to see her city (Lahore) and birthplace. When she was requested to sing in a show for Pakistan Television, she could not refuse and performed live with a painful swallowed mouth and eyes full of tears. Surinder Kaur never disconnected herself from Lahore and Lanhdi Punjabi and used to say that Lahore (Lahnda Punjab) was in her blood and soul—what an honor for the city of Lahore.

Fighting with health issues but traveling all over the world for her performances made Surinder tired and she died on 14 June 2006 but left a legacy of Punjabi singing that is surely well handled by her daughter Dolly Guleria and now granddaughter Sunaini Sharma.

I personally believe that not much has been done so far to document and appreciate her work at the state level and her multi-layered contributions to Punjabi language and culture are yet to be explored. One documentary was produced about her life in 2006 by Doordarshan titled Punjab Di Koyal (Nightingale of Punjab), which is not enough to introduce her to generations to come and to appreciate the dedication of Surinder and her husband towards Punjabi language and culture.

As a singer and songwriter who sang over 2,000 Punjabi songs, Surinder Kaur re-introduced the Punjabi language to Punjabi youth living abroad, particularly in North America and the United Kingdom. It may be remembered that thousands of Sikhs left India for abroad after the 1984 Sikh riots that took place after the assassination of former Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her two Sikh police guards. The generation that was born and brought abroad had technical and social difficulties in learning Punjabi as their first language. The constant music trips of Surinder Kaur and her performances in Canada and the United Kingdom, helped Punjabi youth living there to get connected with the Punjabi language.

Surinder Kaur and her husband both were activists and dedicated their lives for documenting and preserving the Punjabi language and culture therefore she at the pinnacle of her career decided to revert to her roots and left Hindi and Urdu singing. She was singing in the mainstream film industry in Bombay (Now Mumbai) but she opted to get back to Punjab and sang Punjabi songs. There is no doubt that Surinder Kaur made Punjabi contemporary mainstream songs a trendy thing and broke the cliché that the Punjabi language can only be used for folk singing. Her commitment and dedication to her language paved the way for future generations to choose the Punjabi language as a medium of expression in music and films. If Surinder Kaur had not sung contemporary music, today’s Punjabi music and film industry would have believed that Punjabi was only for folk art forms.

Her husband was not only an art lover but an art patronage, he was so invested in Punjabi language, culture, and music that he left his job and got a master’s degree in Punjabi, though he was already a master’s in psychology. He and Surinder Kaur wrote the songs, but these songs are not just trivial love or lust but a documentation of sociology, and anthropology of urban and rural Punjab. Today they can be used as a lens to understand the dynamics of a Punjabi household to Punjabi society at large. Surinder’s songs have layers of meanings encompassing Punjab and Punjabiat, and I personally believe their work was purely academic. They must have been awarded honorary Ph.D. degrees from Punjab universities; either from West Punjab or East Punjab because the credit for popularizing Punjabi songs among Punjabi youth goes to this couple and her reintroduction of Punjabi language to the West then followed by thousands of singers living in the West who opted for Punjabi songs as their genre and UK billboard for years had at least one Punjabi popular song since the 1980s.

There is no doubt that Surinder Kaur left this physical world in 2006 but she would never die because her huge work will keep her alive in the hearts of all Punjabis living in every corner of the world.

“Bulleh Shah Asan Marna Nahi, Gor Paya Koi Hor”

(It is not me in the grave, it is someone else.)

To keep Surinder Kaur alive, special credit goes to her eldest daughter Dolly who documented Surinder’s life and her work is helping writers like me to pen something on Surinder’s life.

As mentioned above, she sang over 2,000 Punjabi songs but some of the best and most eternal songs are mentioned below:

Aa Ja Bhabhiye Dekhiye

AA Waas Manrhe Kol

Aaj di Diharhi Rakh Doli Ni Maa

Aana Hai to AA Jao

Aayi Shagnan di Raat

Addi Rat Tak Main Parhdi

Ae Munda Nira Sanichri

Aj di Diharhi Rakh Doli Ni Maa

Ajab Tamashe Kare Jawani

Akhian Chu Tu Vasda

Ambuva Ke Ped Suhane Kya Kahen

Ankhiyan Milake

Arhio Kag Banere Te Boleya

Azab Tamashe Kare

Baagan Wich Beliyan

Badnaam Na Ho Jaye

Baghan Wich Bolian

Bajare Dasitta

Ban Morni Bagan de Wich

Bari Barsi

Barin Barrin Bolian

Betti Chanan De Olle

Bhabho Kehndi Hai

Bhande Kali Kara Lao

Bittu Mangia Giya

Bolian Te Mahia

Bolian-Bagan Wich

Botal Varga Gall Ve

Bulian Te Cheer

Buri Hoi Lagdi Dharing

Chak Lavo Kaharo Doli

Chan Kithe Guzari Aai Raat

Chanda Re Main Teri Gawahi

Channa Tedi Pagh Walia

Char Geya Mahina Saun

Chare Di Maa

Charh Giya Mahina Saun

Charh Peeng de Holare Naal

Charhde Mirze Khan

Charkhe Ne Soot Layian

Chum Chum Rakho Ni

Dab Wich Adya Kharke

Dachi Walia Morh Muhar Ve

Dard Vichhore Da Haal

Deor de Vyah Vich

Dil Aashiwan Da Shishe Wango

Dil Ke Malik Sun

Dil Leke Bhaga

Dilhion Surmedani

Do Char Din Pyar

Do Pal Beh Ja Kol Ve

Duniya Se Nyari Gori Teri Sasural

Eh Jag Meet Na Dekheo Koee Sorath

Ek Meri Akh Kashni

Ek Wari Aa Ja Haniya

Galian Te Hoyian

Gaman Di Raat Lammi

Ghamaan di Raat Lammi

Chadhi Jawani Rahe Na Gujje

Eddar Kanka Uddar Kanka

Ena Nankiyan de Mooh Chaure

Gol Mashkari Kar Giya

Gora Mukhra Sandoohri Amb

Hae Na Was Ue Aje Na Was Ve

Hae Oh Mere Dhadia Rabba

Hari Main Keh Ke Hari

Harian Ni Malan

Hasse Nal Si Chalavan Phool Marea

Hathin Boota La Ke

Hik Te Lat Ke Rahina

Ik Meri Akh Kashni

Itne Door Ae Huzoor

Jadon di Ho Gai Sadhi

Jattifashiona Ne Patti

Je Jawani Da Maja Janda Reha

Je Mundiya Teri Akh Ve Dukhdi

Jhank Jharokon Se Tu Mehlonwale

Jugni Surinder Kaur

Jutti Kasuri Peari Na Puri

Kabhi Chandni Raaton Mein

Kabhi Panghat Pe Aaja

Kade Khole Whishki

Kag Banere Te Boliyan

Kala Dooria

Kamal Shounk Mahi Da Mainu

Katwa Ke Naiya

Khat Ayea Sohne Sajna Da

Kide Sohne Chan Ni

Kithe Mata Toriyae

Kothe Te AA Mahiya

Kothe Te Ud Kawan

Kut Kut Bajra Main

Ladja Bhrind Ban Ke

Lak Hile Majajan Jandi Da

Langh Aja Pattan Jhana Da

Larh Ja Bhrind Ban Ke

Lari de Ander

Lathe di Chadar

Laye Khabar Na Kujh

Leh Munda Nira Sanichri Aee

Loki Poojan Rub

Luti Heer Ve Gaman

Maar Gayo Re

Machchar Ne Khali Torke

Machiware Wich Baitha

Mahiya Punjabi Lok Geet

Main Apne Dil Ke Haathon

Main College Wich Parhdi

Main Mubarakbaad Dene Aai Hoon

Main Tenu Yaad Awanga

Main Vailan Ho Jaongi

Main Vee Jat Ludhiane Da

Mainu Deor de Vyah Wich Nach Len De

Mainu Heere Heere Akhde

Majhdhar Mein Kashti

Man Ja Balma

Masea De Mele Nu Jana

Mati Khudi Karendi Yaar

Mawan Te Theeyan Ral

Mein Jana Rad De Kol

Menu Heere Heere Aakhe

Mera Long Gawacha

Mere Sada Pardesiya Dhola

Meri Gharhi Te Baran Waze

Milni-Sadde Naven Sajan Ghar Aaye Saloni de …

Mitran Chalia Truck

Modenga Kad Moharan

More Raja Ho

Morenga Kad Muharan

Motor Mitran Di

Muklave Wali Raat

Na Jhirhkin Mutiare

Na Main Hindu Na Main Muslim

Nabhe Wale Theke Diye Band Botle

Najariya Mein Aayi

Ni Main Jana Rab De Kol

Ni Main Kyon Kar Jawan Kabe

Ni Wazdi Dhad Sarangi

Nikki Nikki

O Gori O Chhori

Oh Bada Be Lehaj

Oh Bhara Be Lehaj Ki Kariye

Panje Deor Kuare Bhabhi

Pat Giya Chubare Wali Nu

Pattu Ne Lohrha Mareya

Peke Jaan Waliye

Perin Navin Jhanjhran

Phir Tun Tun Toomba

Pind di Kamayee

Rasia Nimbu Leya De

Ratan Kalian

Ratan Kalian Kalli Nu Daar

Reh Gaye Bha Puchde

Rulenga Syal Wich Kalla

Rut Rangili Hai Suhani Raat Hai

Sada Chirhian Da Chambha

Sadde Ta Vehrhe Mudh Makai

Sade Tan Vehre Mud Makayee Da

Sajre Shareek Ban Gaye

Sapni de Vang

Sarke Sarke Jangdiye Mutiare

Sehtie Ni Sehtie Commentary

Sheesha Lele Behndi

Sherewalia Vanrhaviahawan

Sithniyan Guru Nanak Dev Ji

Suche Ni Mai Vaar

Suhe Ve Cheere Waliya

Sui Ve Sui

Sulan Te Son Gaya

Tande Chupna Chari de Hania

Tar Bina Tumba Vajda

Tere Singha Ne

Tere Utte Rakh Lai Agg

Teri Khatti Lassi Balie

Teri Maa de Nau Kurhian

Thekedaram Na Rakh Leya

Tille Walia

Tu Kahda Lambardar Ve

Tu Mera Bakan Lal

Tun Kahda Lambrdar

Vajida Kaun Saain Noon Aakhe

Vasta E Mera

Ve Gal Sun Deora

Ve Lai de Mainun

Vehrhe Sajna De

Wasta E Mera

Watan Ki Raah Mein

Yaar Lukauna Pejuga