By Anuradha Bhasin Jamwal

A picture is worth a thousand words. Kashmir’s (read as Indian Occupied Kashmir) messy conflict tells us that, quite often, one picture is not enough to reveal its truth. For every image, there is a counter-image, not blunting a thousand words each that they speak but offering a kaleidoscope of a multi-layered and complex narrative.

There is not one but many narratives and many shades – not just black and white. The telling of Kashmir’s story is not simply in the image, or different frames of it, but also in the interrogative gaze of its viewer. Without understanding this reality, the images get trapped as props in a propaganda war.

The horrifying incident of the violent death of a man in gunfire in Sopore on Wednesday (July 1, 2020) morning is instructive. A CRPF personnel was also killed and three others were injured in the incident. According to police, the militants, who were hiding in a nearby mosque, suddenly opened fire, triggering an encounter. While the man’s family has alleged that he was shot dead by the security forces to avenge the killing of their colleague, police have refuted the charge. A senior police officer is reported to have said, “most probably, he was shot by the militants” in the cross-fire. But, he offered no plausible explanation for his conclusion.

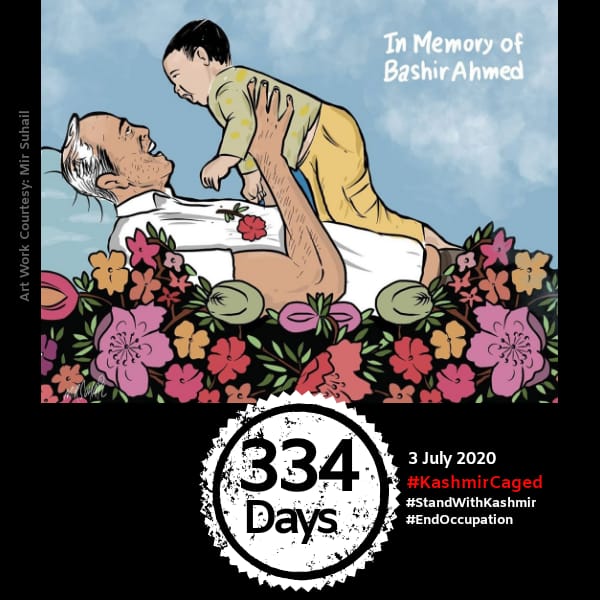

Soon after the encounter, where the man, Bashir Khan, accompanied by his three-year-old grandson was seemingly caught, a heart-wrenching photograph of the little boy sitting on the blood-splattered body of his grandfather and crying, went viral. A photograph of the boy being carried by the police and yet another inside a police vehicle with a gifted arsenal of candies and chocolates, probably offered by the police to console him, were also in circulation.

To the orgasmic delight of the likes of Sambit Patra, the photograph was a godsent boon to be used as a propaganda tool to vilify Kashmiris. Patra shared the picture on his twitter account with the caption: “PULITZER LOVERS??”

No word of sympathy, no expression of horror at the sight but just a simple dig at the Pulitzer Prize in Feature photography won by three AP journalists from Jammu and Kashmir for showcasing, through a set of images, the sufferings of the people of Jammu and Kashmir that his government wishes to paper over with the paradigm of pretended normalcy.

Journalist-writer, Aatish Taseer’s tweet aptly sums up the despicable nature of such a response: “If a single tweet could capture the utter moral destitution that Modi has wrought in India, this is it. Here is his party spokesman glorying in the sight of a little boy with the body of his dead grandfather, killed in crossfire in Kashmir.”

Sensitive netizens including many Kashmiris who had spent the morning sharing, with a sense of horror and pain, the image of the little boy and the tragic import of its message were aghast when Patra made his disgusting remarks in the afternoon.

The complex war of viral images is far from over. From the set of pictures in circulation, that must have missed Patra’s eagle eye, was another of security personnel standing over Khan’s dead frame, his feet virtually touching it. This became viral by the evening to present a counter view.

The state, of course, is expected to be a more responsible entity but exploitation of a tragedy and a minor’s vulnerability does not end at that door. The family of Bashir Khan, which maintains that he was killed by the security forces, has not said how it reached such conclusions. But by Thursday morning, Kashmir’s social media was taken in by a storm of videos featuring the boy, saying the “Police shot” to questions being asked by some “unseen” adult. There is not one but at least two videos, one where he is answering queries in his child-like innocence to a woman and another in which he rephrases his words, “he was killed by police”, in response to similar queries by a man.

Two questions prod the mind after watching these videos. One: Why is the boy’s agony being multiplied by subjecting him to the torture of making him recall something and catching it on camera, several times. (Whoever did it, obviously did it with the consent of the family.) Second: Can the boy’s version be treated as credible? He appears to be a prime witness of the incident and his version cannot be ignored. But, by showcasing him in these circulated videos, the boy has become more vulnerable and the sanctity of his testimony is jeopardised.

There are related questions. The incident can easily be viewed in the backdrop of allegations of institutional violence by the state and botched up investigations. Did this make it imperative to record his statement as evidence? Or, could it have been done more discreetly?

Amnesty International, slammed the police for releasing the picture of the three-year-old boy. “By disclosing the identity of a minor witness of a crime, Kashmir Zone Police stands in violation of Article 74 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015. It is also a breach of the “best interests of the child” principle as required to be the basis of any action by the authorities under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which India is a state party,” it said. What is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander! Could the same principle also apply to those who created these videos and circulated them?

There are no easy answers. The moral and ethical questions were as much relevant when the world saw the horrifying images of children bearing the brunt of violence across the globe, whether it was Alan Kurdi, three-year-old refugee boy from Syria whose body was discovered on the shores of Turkey in 2015 or years before that of a 9-year-old girl running away from the Napalm bombings during the Vietnam war in 1972. Whatever be the debate around the compass of morality, such images have also pricked the world conscience and prompted it to respond more responsibly.

What makes the Sopore boy’s case different is that more than needling someone’s dead conscience, he appears to have become an object for politics and propaganda when there is dearth of clarity on who is responsible for the tragedy.

Kashmir is filled with stories of civilians killed by state agencies, militants, and innocent bystanders in cross-firing. The majority of these stories remain contested, uninvestigated and the truth obfuscated forever despite some images, despite some facts and despite some evidence.

Like in most cases, we are left with images and some questions. The entire set of images speak in this particular case speak to us and compel us to raise these pertinent questions.

In which order does one see these images?

Bashir Ahmed Khan and his grandson were traveling in a car. His body is lying straight on his back on the roadside, his face up, his white shirt bloodstained. There are no blood trails to be seen anywhere around, suggesting that he was on the road when he was killed. Why was he out of his car? Would a natural instinct of someone caught in cross-firing be to duck inside the car or move out and run for safety? Did he move out of his own volition? Was he asked by the security forces to come out? Why?

Were there other eye-witnesses, more people caught on the road at the time of the encounter?

Since there were no journalists present, and if no civilians were around, who was clicking the pictures and why when cross-firing was going on? What purpose does their circulation achieve?

This question assumes even more importance when you stare into what appears like the first two images – that of the child sitting on the corpse, strangely, his back to the dead man’s face, and the next of him moving from the body towards gun-totting security personnel, signaling him from the corner he is positioned in, next to the wall, presumably revealing that he is in combat mode. So much for the rescue theory!

These two images leave behind more conundrums. Between these two pictures, and perhaps a little before, there are several moments that remain un-captured. Presuming that Bashir Khan was shot on the road and immediately fell dead on his back, how much time passed by between the several moments – the gunshot, the boy sitting backwards to the deceased’s face, the security man in the corner waving to the boy, and the boy moving towards him. All this while, the firing was going on and someone was clicking pictures? And, strangely not making a video!

Zoom these pictures and one can spot dust on the trousers of Bashir Khan, signs of either being dragged or having fallen face down. The image clearly reveals signs of scraping through the dust. The body is face up. (His car in another image is towards his feet. If he was running, which direction was he running?) And more, the security man taking cover, next to the wall, is missing in the first frame. Plausible that during an encounter, combatants shift positions for cover or for better strategic advantage but strange that during all this commotion, a boy sits on the corpse and then moments away calmly walks towards the personnel. Was there really firing going on when these pictures were clicked?

If the incident is horrifying, the politics around it also belies the basic principles of humanity. There are only two main things to read in those sets of images. One is the vulnerability of children in Kashmir’s conflict. Second, are the unaddressed questions that we must continue to ask.

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this article/Opinion/Comment are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Dispatch News Desk (DND). Assumptions made within the analysis are not reflective of the position of Dispatch News Desk.