By Saqlain Imam

On August 5, 2019, in the charged aftermath of the Pulwama attack, the Government of India made a historic and controversial move by abrogating Articles 370 and 35A of the Constitution, effectively stripping Jammu and Kashmir of its special status. The decision, hailed by the ruling establishment as a definitive step toward integrating the region and ending the Kashmir dispute once and for all, was executed with a sweeping constitutional maneuver and an unprecedented security clampdown.

However, six years later, the grim massacre at Pahalgam in 2025, followed by a short but volatile military confrontation between India and Pakistan, and the unexpected diplomatic intervention by U.S. President Donald Trump, have laid bare a harsher reality: rather than resolving the Kashmir dispute, the abrogation may have only buried it temporarily, allowing it to erupt again with more urgency and global consequence. Far from settling down, the Kashmir question now appears even more intractable—haunted by history, inflamed by geopolitics, and still awaiting a just resolution.

For decades, Articles 370 and 35A stood as constitutional bedrocks, affirming Jammu and Kashmir’s unique status within the Indian Union. Article 370 conferred special autonomy, allowing the region to retain its own Constitution and governance structure; Article 35A, an incidental offspring, restricted land ownership, employment, and settlement rights to “permanent residents.” These provisions were not merely legal artifacts; they were manifestations of solemn commitments made during Jammu and Kashmir’s accession to India in 1947. In essence, they were designed to safeguard the identity, autonomy, and distinctiveness of Kashmir within a federal union.

On August 5, 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government shattered that status quo. Employing Presidential Order CO 272 to reinterpret “Constituent Assembly” in Article 370(3) as the current Legislative Assembly, and acting under President’s Rule, the Centre asserted it possessed the authority to enact the abrogation. The next day, CO 273 rendered Articles 370 and 35A dormant. At the same time, the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act bifurcated the former state into two Union Territories—Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh—effectively dissolving statehood in favour of central authority, as permitted by Article 3 of the Constitution.

This was more than a constitutional sleight of hand. It was a moment of radical rupture: the first time in the history of independent India that a full-fledged state was downgraded into a Union Territory, stripping its people of legislative autonomy, executive command, and democratic representation in key areas of governance. Even more strikingly, the state was divided into two separate units without the consent of its people or their elected representatives, who were at the time incarcerated or under house arrest. To many, this was not merely administrative restructuring — it was a modern re-enactment of colonial centralism, with Kashmir reduced to a governed territory rather than a constituent unit of a democracy.

From State to Colonized Territory: A Post-Colonial Critique

The bifurcation of Jammu and Kashmir into Union Territories — Jammu & Kashmir with a legislative assembly and Ladakh without one — is constitutionally unprecedented. While the Indian Constitution under Article 3 allows Parliament to reorganize states, no other state in Indian history has been demoted into a Union Territory against the will of its people.

This act, legal on the surface, violates the very spirit of Indian federalism. It transforms a federal partner into an administrative dependency. The Union Territory structure, wherein the Lieutenant Governor is appointed by and reports directly to the central government, essentially removes all meaningful local sovereignty. In the case of Ladakh, which has no legislative assembly at all, this lack of representation is total.

As constitutional scholar Gautam Bhatia pointed out, the move “amounts to treating the people of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh not as citizens but as subjects.” It reawakens historical memories of imperial subjugation, particularly the way British India was governed without local consent. India, once a colony governed by viceroys and governors-general from London, now enacts a disturbingly similar paradigm over Kashmir.

In the absence of elections, with a suspended legislature and an unelected administrator at the helm, Kashmir has become the only region in India without a representative government. Dr. Noor Ahmad Baba, a prominent Kashmiri political scientist, remarked that “if democracy is ruled by the people, then Kashmir has been pushed out of that definition entirely.”

This centralised imposition recalls the logic of colonialism — governing a people without their consent, without their participation, and often against their will. Kashmir today remains under a form of constitutional martial law — ruled not by the mandate of its people, but by the decree of a distant Parliament.

Consequences and Clampdown

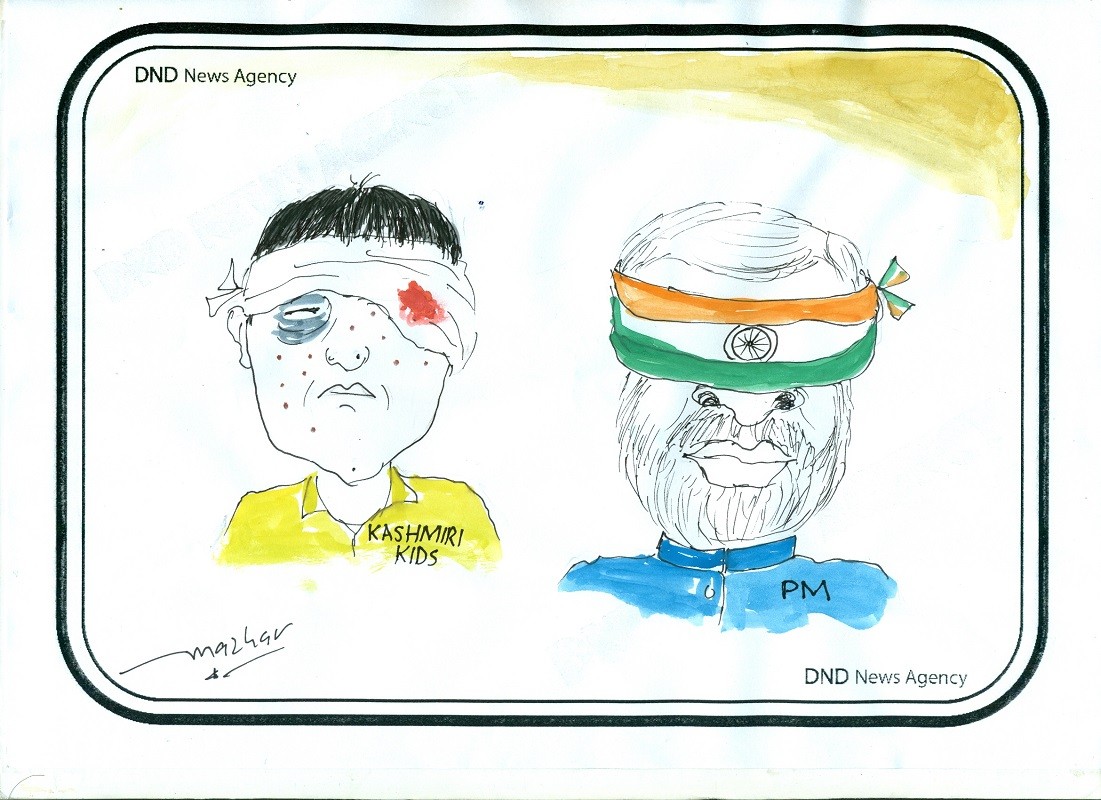

The immediate aftermath of the abrogation was stark: a heavy military lockdown was imposed, schools and businesses closed, and communication networks — including internet and mobile services — were blacked out for months. The government deployed over 38,000 additional paramilitary personnel in the valley. Almost all major political leaders — including three former Chief Ministers, Farooq Abdullah, Omar Abdullah, and Mehbooba Mufti — were placed under preventive detention, some for nearly a year under the Jammu & Kashmir Public Safety Act.

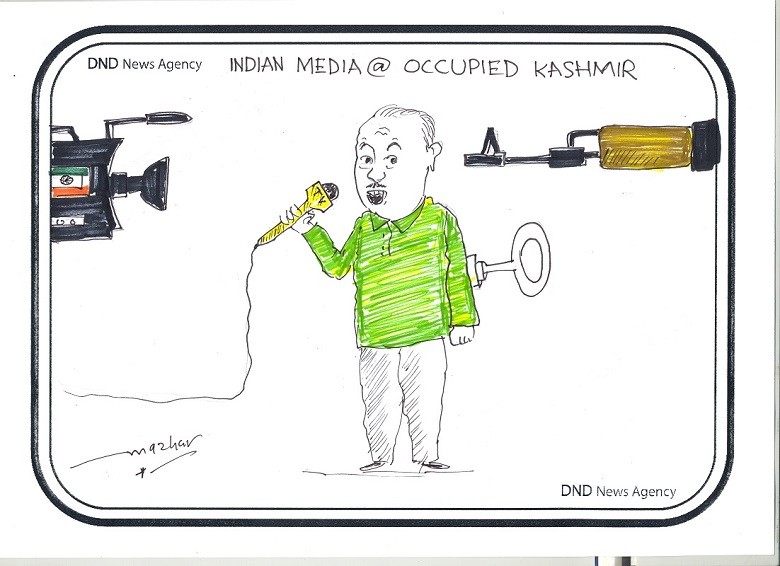

Civil liberties were severely curtailed. Media organizations faced harassment and censorship; journalists were summoned by police for critical reporting. Many human rights groups, including Amnesty International, reported widespread violations, including arbitrary arrests, denial of legal access, and reports of torture. The United Nations Human Rights Office expressed concern, calling on India to respect the rights of the Kashmiri people.

The psychological impact on the local population has been immense. A pervasive sense of disempowerment, humiliation, and betrayal has taken root. Many Kashmiris now see the Indian state not as a partner in governance, but as an occupying force.

The Legal Challenge in the Supreme Court

Petitions challenging the abrogation were filed by over 20 individuals and organizations, including political parties like the National Conference and People’s Democratic Party. Their arguments revolved around the assertion that Article 370 had become permanent after the dissolution of the J&K Constituent Assembly in 1957, and therefore could not be unilaterally repealed. They also argued that President’s Rule cannot be used to effect irreversible constitutional changes, especially not the abolition of a state’s autonomy.

Another major contention was that downgrading a state to a Union Territory violates the basic structure of the Constitution, particularly the principle of federalism, which has been reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in several landmark judgments, including the Kesavananda Bharati case.

The government countered that Article 370 was always temporary — a transitional arrangement that could be repealed. They claimed that Parliament could legally act as the J&K Legislative Assembly under President’s Rule and that the reorganization of states was a matter of political necessity and constitutional procedure.

In December 2023, the Supreme Court upheld the abrogation. Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud led the bench in declaring that Article 370 was temporary, that Parliament was within its rights to abrogate it during President’s Rule, and that the Reorganisation Act did not violate the Constitution.

Experts Slam the Verdict: “A Judicial Endorsement of Executive Overreach”

Legal experts and constitutional scholars roundly criticized the ruling. Gautam Bhatia noted that the Court “did not engage seriously with the manner in which the abrogation was carried out — through executive manipulation rather than democratic debate.” He described the judgment as “formalistic,” arguing that it failed to safeguard India’s federal spirit and opened the door for the “executive to rewrite the Constitution in moments of political convenience.”

Zaid Deva, a Kashmiri legal scholar, described the verdict as “a historical whitewash,” warning that the judgment erases both constitutional history and the political will of Kashmiris. He argued that “the decision legitimizes a colonial model of governance, where an unelected center imposes itself on a silenced region.”

Justice (Retd.) A.P. Shah, former Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court, stated in a public forum: “This judgment will be remembered not for its constitutional clarity but for the silence it enshrines — the silence of Kashmir, and the silence of dissent.”

Human rights activist Vrinda Grover added that the Court’s decision showed “a complete abdication of the judiciary’s role as a check on executive excess.”

Where Kashmir Stands Today

Despite repeated promises from the Modi government, no elections have been held in Jammu and Kashmir as of August 2025. While Ladakh remains without a legislature, the Jammu & Kashmir Union Territory operates under an unelected Lieutenant Governor. Former Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah recently lamented that “we are ruled by a viceroy now”, echoing colonial comparisons.

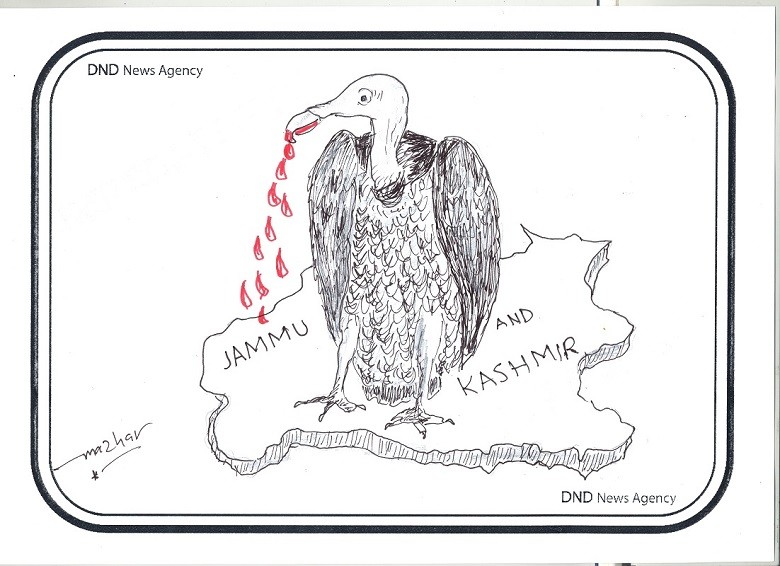

The situation remains volatile. The security presence continues to be heavy. Public disillusionment has deepened. Dialogue between New Delhi and Kashmiri political parties remains frozen. The disbandment of statehood and dismantling of autonomy have, for many Kashmiris, confirmed their fears that India is not interested in integrating Kashmir as an equal partner, but in ruling it as a possession.

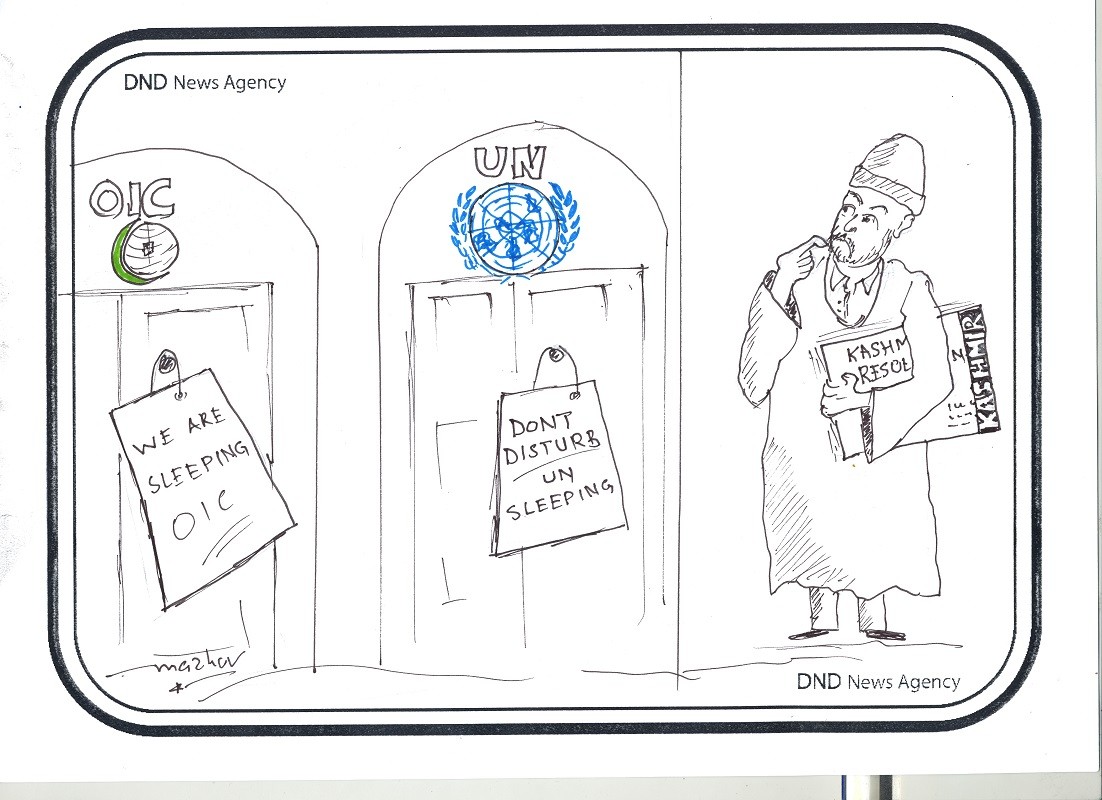

Internationally, the dispute has lost momentum. Pakistan continues to raise it diplomatically, but with little effect. The UN and Western governments have expressed concern over human rights violations, but have not taken substantial action.

What remains is a constitutional vacuum — a region without a voice, governed by the shadows of executive power and judicial approval. The abrogation of Article 370 and the downgrading of statehood have fundamentally altered the Indian federal landscape and deeply scarred Kashmir’s relationship with the Indian Union.

The abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A, and the bifurcation of Jammu and Kashmir, mark more than a constitutional shift; they mark the transformation of a political compact into a unilateral imposition. The Supreme Court’s validation of this act has institutionalized a version of federalism in which the Centre can unmake states, discard autonomy, and silence dissent without consequence.

In this new paradigm, Kashmir is not a partner in Indian democracy, but a governed territory — reminiscent of the very colonial legacy India claims to have shed. And unless the Union restores not just elections, but dignity, trust, and a real stake in governance, the wounds inflicted in 2019 will not easily heal. The law may have spoken, but justice — and reconciliation — remain elusive.

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this article/Opinion/Comment are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the DND Thought Center and Dispatch News Desk (DND). Assumptions made within the analysis are not reflective of the position of the DND Thought Center and Dispatch News Desk.